Truth in Painting: Cézanne’s Portraits at the National Gallery of Art

One can hardly overstate the significance of Paul Cézanne (1839-1906), an artist who not only transformed French painting, but in many ways invented modern art: “The father of us all,” as Picasso observed. To be a painter in the twentieth-century one had to come to terms with Cézanne – an artist whose work forces upon us the question of what it means to be a painter. For Cézanne, it was nothing less than to confront the mystery of the visible, the vitality and interpenetration of objects, the paradoxical nature of being itself.

The National Gallery of Art in Washington D.C. is currently exhibiting a generous selection of Cézanne’s portraits, offering a window into the artist’s development, his readiness to experiment, his unflinching honesty and tireless commitment as a painter: “I want to die painting,” he would say, “I am probably only the primitive of a new art.”

From the town of Aix-en-Provence, Cézanne was a man of independent means, and therefore did not require finding buyers for his work; he was able to devote his life to the solution of those artistic problems that consumed and obsessed him. He would say that he wanted to paint “Poussin from nature” – which presumably meant that he wanted to attain the perfect balance, harmonious design, and substantiality of the old masters, who he studied religiously at the Louvre, while remaining true to the discoveries of the Impressionists, whose exhibitions he would take part in as a young man. In short, to bring together the order and necessity of the old masters, with the fidelity to nature and the artist’s sensations that distinguished the great Impressionist painters of his generation – including, Monet, Renoir and Pissaro.

Not unlike Rembrandt, Cézanne painted self-portraits throughout his career, in what constituted a kind of running autobiography. The exhibition presents a number of these, including the bold, brash Self-Portrait with a Landscape Background (1875), painted when he was thirty-six years old. Cézanne has accentuated, even exaggerated his prematurely balding head; his side locks are wild and unkempt, while the bushy mustache and beard entirely covers over the mouth. He has no need for words: his arched brows accent the piercing eyes, giving the work a brazenly dramatic flair. He bellows and roars with those magnificent eyes and V-shaped brow, atop which sits a massively rounded forehead. We seem to be face to face with a painter who is aware of his power and wants to make us aware of it too.

Boy in a Red Waistcoat (1888-1890) is another standout in the show, one of a series of paintings Cézanne did of a young boy dressed in the garb of an Italian peasant. The contrapposto of the standing figure, evocative of classical sculpture, is unusual among Cézanne’s portraits, and lends the romantic youth a certain élan and dash. Perhaps what is most striking is the use of color – the pinks and greens and blues that respond in a varied and complex harmony with the lively red of the boy’s vest. Color was all-important for Cézanne: for him, the painter ‘spoke in colors’. What Cézanne said of Veronese could have just as easily been said of him: “his colors dance.” One is “reinvigorated by them. You are born into the real world. You become yourself. You become painting…” At the same time, colors existed only in relation to each other – for Cézanne, their significance was inseparable from their relationships, so that each spot seems to have “a knowledge of every other.”

A substantial portion of the show is devoted to the portraits of Cézanne’s wife Hortense, of which the painter did over thirty. While generally not unsympathetic, neither do these pictures flatter their subject, who is sometimes quite plain in her appearance. In more than a few we encounter a frank, even startling mixture of severity and impatience verging on outright displeasure.

Madame Cézanne in a Red Dress (1888-1890) – on loan from the Metropolitan Museum of Art – is an extraordinary painting, in which we find the subject seated in an elaborately furnished interior. Like so many of these works it is a rather strange and somewhat disconcerting portrait, all the more so for the odd tilt of the sitter and her surroundings, as if everything within the frame is in movement and in danger of sliding off the canvas entirely. Hortense wears a typical bourgeois housedress, however the vital red tones lend credence to Cézanne’s claim that no one could paint red as he did.

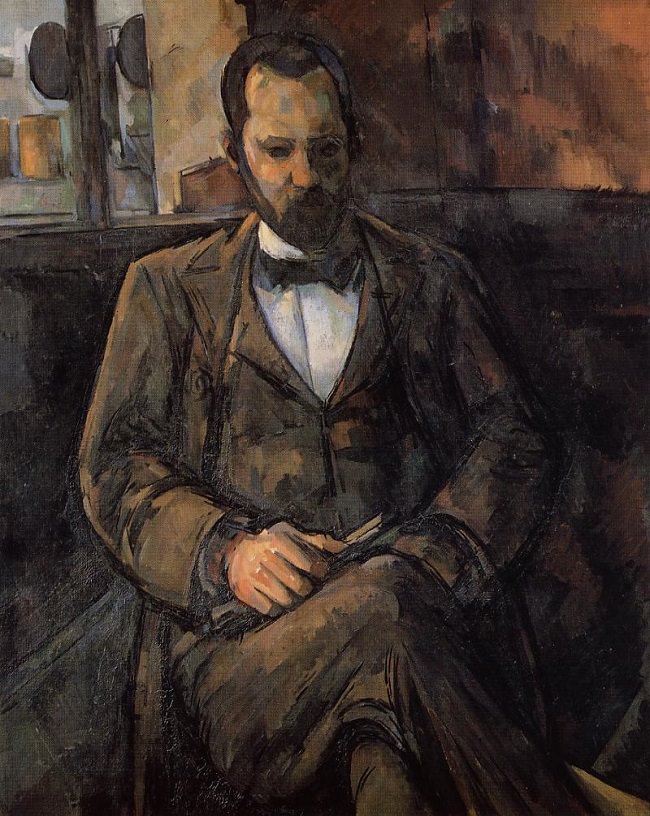

The portrait of art dealer Ambroise Vollard (1899) is undoubtedly among the most majestic and legendary of the works in this exhibition. It took some one hundred and fifteen sessions of posing to see the painting through, and still the piece was ultimately left unfinished – like so many of Cézanne’s canvases. Indeed, Giacometti went so far as to say that, “[Cézanne] never really finished anything… That’s the terrible thing: the more one works on a picture, the more impossible it becomes to finish it.”

In the works of his later years, Cézanne would often leave substantial portions of the canvas exposed. This is evident in his landscapes, a handful of which are housed in the National Gallery. “The landscape,” he said “thinks itself in me, and I am its consciousness.” The seeing of the painter was not the inspection of an in-itself world, for Cézanne – hence, his abhorrence of the photographic eye – but a vision that occurs in him: “Nature is on the inside,” he would say. The painter’s task is to trace the coming-to-itself of the visible – the way in which the mountain makes itself seen by the painter. The painter does not produce simply another thing: his achievement consists in unfolding the carnal essence of the thing – a visible to the second power, as it were.

“Nothing is beautiful except what is true,” Cézanne once said, “and only true things should be loved.” As the philosopher Jacques Derrida put it: “The truth in painting is signed Cézanne.” Perhaps it is this above all else that makes him the indispensible painter for our times, this era of so-called ‘post-truth.’ For Cézanne “painting was truth telling or it was nothing.” That is what it meant to paint from nature, to be primitive, to be free from all affectation, to be like those “first men who engraved their dreams of the hunt on the vaults of caves…” This is why we need to look and look again at Cézanne. And it is perhaps best that he has come to the National Gallery, to D.C., but a stone’s throw away from where truth is daily made a mockery of, and lies are proffered with breathtaking ease.