When did we become fully human? What fossils and DNA tell us about the evolution of modern intelligence

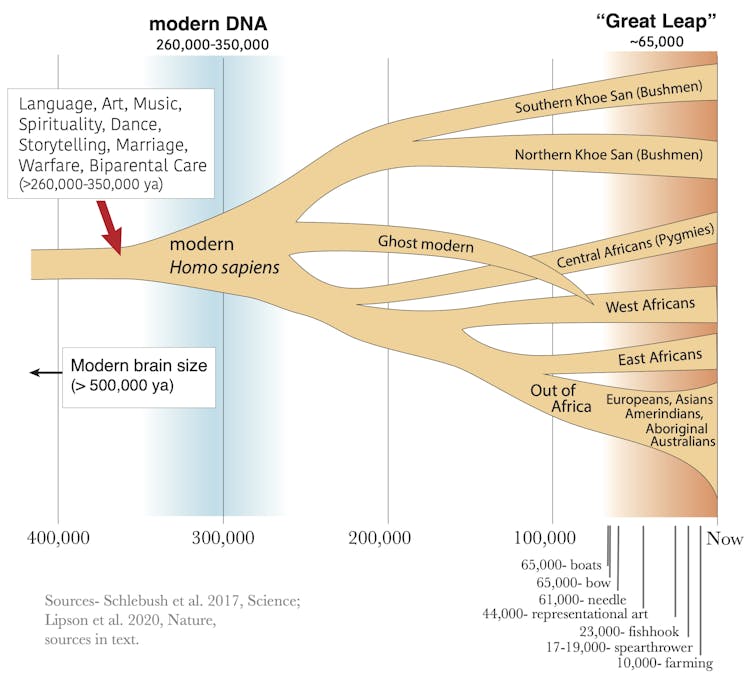

When did something like us first appear on the planet? It turns out there’s remarkably little agreement on this question. Fossils and DNA suggest people looking like us, anatomically modern Homo sapiens, evolved around 300,000 years ago. Surprisingly, archaeology – tools, artefacts, cave art – suggest that complex technology and cultures, “behavioural modernity”, evolved more recently: 50,000-65,000 years ago.

Some scientists interprAdd Editor Letteret this as suggesting the earliest Homo sapiens weren’t entirely modern. Yet the different data tracks different things. Skulls and genes tell us about brains, artefacts about culture. Our brains probably became modern before our cultures.

The “great leap”

For 200,000-300,000 years after Homo sapiens first appeared, tools and artefacts remained surprisingly simple, little better than Neanderthal technology, and simpler than those of modern hunter-gatherers such as certain indigenous Americans. Starting about 65,000 to 50,000 years ago, more advanced technology started appearing: complex projectile weapons such as bows and spear-throwers, fishhooks, ceramics, sewing needles.

People made representational art – cave paintings of horses, ivory goddesses, lion-headed idols, showing artistic flair and imagination. A bird-bone flute hints at music. Meanwhile, arrival of humans in Australia 65,000 years ago shows we’d mastered seafaring.

This sudden flourishing of technology is called the “great leap forward”, supposedly reflecting the evolution of a fully modern human brain. But fossils and DNA suggest that human intelligence became modern far earlier.

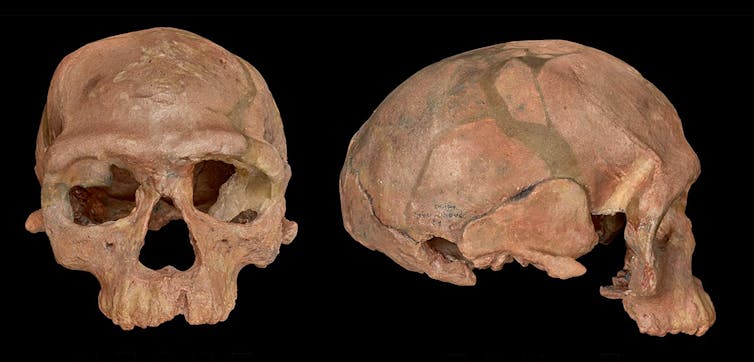

Anatomical modernity

Bones of primitive Homo sapiens first appear 300,000 years ago in Africa, with brains as large or larger than ours. They’re followed by anatomically modern Homo sapiens at least 200,000 years ago, and brain shape became essentially modern by at least 100,000 years ago. At this point, humans had braincases similar in size and shape to ours.

Assuming the brain was as modern as the box that held it, our African ancestors theoretically could have discovered relativity, built space telescopes, written novels and love songs. Their bones say they were just as human as we are.

Because the fossil record is so patchy, fossils provide only minimum dates. Human DNA suggests even earlier origins for modernity. Comparing genetic differences between DNA in modern people and ancient Africans, it’s estimated that our ancestors lived 260,000 to 350,000 years ago. All living humans descend from those people, suggesting that we inherited the fundamental commonalities of our species, our humanity, from them.

All their descendants – Bantu, Berber, Aztec, Aboriginal, Tamil, San, Han, Maori, Inuit, Irish – share certain peculiar behaviours absent in other great apes. All human cultures form long-term pair bonds between men and women to care for children. We sing and dance. We make art. We preen our hair, adorn our bodies with ornaments, tattoos and makeup.

We craft shelters. We wield fire and complex tools. We form large, multigenerational social groups with dozens to thousands of people. We cooperate to wage war and help each other. We teach, tell stories, trade. We have morals, laws. We contemplate the stars, our place in the cosmos, life’s meaning, what follows death.

The details of our tools, fashions, families, morals and mythologies vary from tribe to tribe and culture to culture, but all living humans show these behaviours. That suggests these behaviours – or at least, the capacity for them – are innate. These shared behaviours unite all people. They’re the human condition, what it means to be human, and they result from shared ancestry.

We inherited our humanity from peoples in southern Africa 300,000 years ago. The alternative – that everyone, everywhere coincidentally became fully human in the same way at the same time, starting 65,000 years ago – isn’t impossible, but a single origin is more likely.

The network effect

Archaeology and biology may seem to disagree, but they actually tell different parts of the human story. Bones and DNA tell us about brain evolution, our hardware. Tools reflect brainpower, but also culture, our hardware and software.

Just as you can upgrade your old computer’s operating system, culture can evolve even if intelligence doesn’t. Humans in ancient times lacked smartphones and spaceflight, but we know from studying philosophers such as Buddha and Aristotle that they were just as clever. Our brains didn’t change, our culture did.

That creates a puzzle. If Pleistocene hunter-gatherers were as smart as us, why did culture remain so primitive for so long? Why did we need hundreds of millennia to invent bows, sewing needles, boats? And what changed? Probably several things.

First, we journeyed out of Africa, occupying more of the planet. There were then simply more humans to invent, increasing the odds of a prehistoric Steve Jobs or Leonardo da Vinci. We also faced new environments in the Middle East, the Arctic, India, Indonesia, with unique climates, foods and dangers, including other human species. Survival demanded innovation.

Many of these new lands were far more habitable than the Kalahari or the Congo. Climates were milder, but Homo sapiens also left behind African diseases and parasites. That let tribes grow larger, and larger tribes meant more heads to innovate and remember ideas, more manpower, and better ability to specialise. Population drove innovation.

This triggered feedback cycles. As new technologies appeared and spread – better weapons, clothing, shelters – human numbers could increase further, accelerating cultural evolution again.

Numbers drove culture, culture increased numbers, accelerating cultural evolution, on and on, ultimately pushing human populations to outstrip their ecosystems, devastating the megafauna and forcing the evolution of farming. Finally, agriculture caused an explosive population increase, culminating in civilisations of millions of people. Now, cultural evolution kicked into hyperdrive.

Artefacts reflect culture, and cultural complexity is an emergent property. That is, it’s not just individual-level intelligence that makes cultures sophisticated, but interactions between individuals in groups, and between groups. Like networking millions of processors to make a supercomputer, we increased cultural complexity by increasing the number of people and the links between them.

So our societies and world evolved rapidly in the past 300,000 years, while our brains evolved slowly. We expanded our numbers to almost 8 billion, spread across the globe, reshaped the planet. We did it not by adapting our brains but by changing our cultures. And much of the difference between our ancient, simple hunter-gatherer societies and modern societies just reflects the fact that there are lots more of us and more connections between us.

Nick Longrich, Senior Lecturer in Evolutionary Biology and Paleontology, University of Bath

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.